Resources

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Expand

Collapse

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Inverted Selective Plane Illumination Microscopy (iSPIM) is a type of light sheet fluorescence microscopy technique developed by Yicong Wu and Hari Shroff (both at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB)) and their colleagues at Yale University and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre which adds plane illumination functionality to any inverted microscope (PNAS, USA, 2011, Oct 25; 108 (43) 17708-17713). This light sheet approach is used to image the neural development of the nematode C. elegans. iSPIM allows one to achieve very fast non-invasive imaging of living samples, facilitating the inspection of live neurodevelopmental events and paving the way for a 4D dynamic neurodevelopmental atlas in C. elegans. The iSPIM sample is prepared on a coverslip, the same as it is for conventional microscopy, therefore making this a transferable method for many neurobiology and developmental laboratories.

With only 302 neurons, ~7000 synapses and an available and comprehensive connectivity map, C. elegans is an excellent model for this research. The molecular mechanisms that control neurodevelopment decisions in the nematode are well conserved throughout evolution and studies in C. elegans have contributed to a clear understanding of neuroblast migration and axon guidance. As described in (PNAS, USA, 2011, Oct 25; 108 (43) 17708-17713) the technique of iSPIM allowed Shroff and his team to continuously image the nematode embryo, scanning volumes every 2 s for the entire 14 h of embryogenesis with no detectable phototoxicity. Additionally, two colour iSPIM images were merged to visualize neurodevelopmental dynamics.

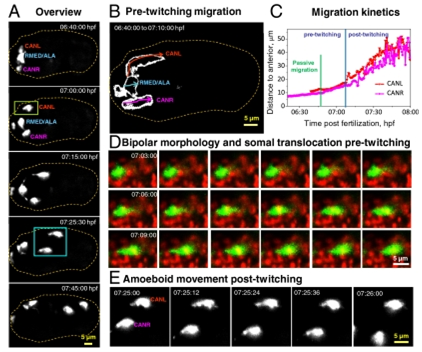

Fig 1. Neuronal morphology and migration through early twitching. (A) Selected maximum-intensity projections of ceh-10p:GFP, highlighting migration of neurons after expression of GFP, through onset of early twitching. The outline of the embryo is indicated by the dotted line. (B) Outlines of the migratory path of individual neurons before embryonic twitching. (C) Migration kinetics of CANs from the dataset shown in A, through early twitching. 3D displacements are measured from the anterior tip of the embryo. (D) An example of somal translocation before twitching from a dual-color iSPIM dataset. (E) Higher-magnification view of the blue boxed region in A, showing amoeboid movement of CANs posttwitching as neurons migrate posteriorly. Dual-color images in D were acquired from a representative embryo at 12 vol/min. In all images, anterior is Left and posterior Right.

Four neurons were investigated during early embryogenesis, each expressing transcription factor CEH-10/Chx10 and the cell migration and neurite outgrowth decisions made by these neurons throughout embryogenesis was also examined. The four neurons investigated were CANL, CANR, RMED and ALA. Shroff and his team found that CANs use somal translocation and amoeboid movement as they translocate to their final position (Fig 1). Using iSPIM to image these neurons they were also able to visualize axon guidance and growth cone dynamics as neurites circumnavigate the nerve ring of the body of the worm to reach their targets.

The PNAS article states that Shroff and his colleagues chose to develop iSPIM for their studies for two main reasons. Firstly, neurulation in the embryo is accompanied by fast movement and twitching, requiring faster volumetric imaging rates to avoid the artifacts induced by motion blur. Secondly, conventional 4D imaging technologies such as point scanning confocal or 2-photon microscopes fail to provide the necessary signal rates. To overcome these hurdles Shroff and his team developed iSPIM which is fast, minimally invasive and can be used to study nematode embryos.

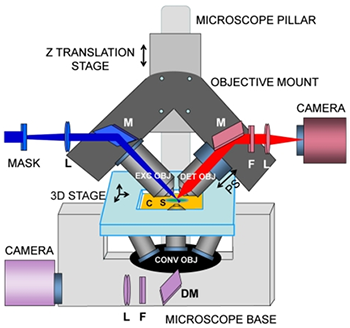

Fig 2. iSPIM, plane illumination on an inverted microscope base.

iSPIM replaces the illumination pillar of an inverted microscope with a mechanical housing for two objectives that illuminate the sample with a light sheet and collect the resulting fluorescence (Fig 2). By rapidly translating the light sheet through the sample, rapid volumetric image collection is enabled without requiring specimen movement. The choice of objectives is mechanically constrained by the need to place them at 90° without steric interference between each other or the sample. High NA (0.8) objectives with long focal lengths (3.5 mm) were chosen for this particular study. The samples can be mounted in the conventional way on rectangular coverslips and can be translated using an automated 3D stage.

[Disclaimer: The NIH, as a US Government agency, does not endorse any particular company, product or service.]

Both EMCCD and sCMOS cameras can be used for light sheet microscopy techniques. For this particular study the researcher chose to use an EMCCD for its high resolution, speed and sensitivity.

The iXon EMCCD camera series work well for iSPIM where the electron multiplication can be utilised for the weakest fluorescent samples and the fast frame rates with the “Crop Sensor” mode allow the capture of dynamic events. Facilitated by a fundamental redesign, the latest iXon Life 888 camera takes the largest back-illuminated 1024 x 1024 frame transfer sensor and overclocks readout to 30 MHz, pushing speed performance to an outstanding 26 fps (full frame), whilst maintaining quantitative stability throughout. The significant speed boost offered in the iXon Life 888 facilitates a new level of temporal resolution to be attained, ideal for speed challenged low-light applications such as iSPIM. Furthermore, the iXon Life has been to reduce the price point necessary for accessing EMCCD technology.

However, sCMOS cameras such as the Andor Neo, Zyla and new Sona series are also highly applicable for such applications. These sCMOS cameras offer larger fields of view and high resolution when compared to the EMCCD cameras, along with higher frame rates. The small pixel size of 6.5 micrometers ensures sufficient oversampling of the PSF (pointspread-function), at the objective magnifications typically used for developmental studies. These sCMOS cameras are sensitive enough for most applications while the high speeds and large fields of view facilitate the live acquisition of dynamic events which take place during embryogenesis.

Date: May 2020

Author: Dr Alan Mullan

Category: Application Note