Resources

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Expand

Collapse

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

The orbital environment has reached a critical density. To manage the exponentially growing threat of space debris, operators rely on Space Situational Awareness (SSA) for collision avoidance. However, current orbital propagation models face a fundamental data deficit. They often rely on Two-Line Element (TLE) sets.

A TLE is a standardised data format that provides a satellite’s orbital position and velocity at a specific point in time. While TLEs are sufficient for general tracking, they lack precision regarding an object’s physical characteristics.

Accurate orbit prediction requires precise modelling of non-gravitational forces, specifically atmospheric drag and solar radiation pressure [1]. These forces are non-linear and heavily dependent on the object’s size, shape, and orientation – parameters that are often unknown for debris or defunct satellite [2]. Without this “characterisation” data, the position of a satellite can drift significantly from its predicted path.

Ground-based optical telescopes offer a solution for characterising these objects, but they are limited by the medium they look through: the Earth’s atmosphere. Even if these telescopes are usually located in altitude to avoid the most of atmospheric turbulences, they are still concerned by higher atmospheric layers.

The atmosphere is a dynamic, turbulent system. Variations in temperature and wind shear create constantly changing pockets of air with different refractive indices. As light from a satellite passes through these pockets, the wavefront is distorted.

For a large aperture telescope (e.g., 1 meter), this turbulence effectively destroys the instrument’s theoretical resolution. While the telescope should be “diffraction-limited” (resolution defined by λλ/DD ), the atmosphere limits it to the “seeing limit” (defined by the Fried parameter, rr0 ) [1]. In practice, this reduces a complex, multi-panel satellite to a blurry, fluctuating blob, making identification impossible.

Adaptive Optics (AO) systems solve this by measuring the wavefront distortion and correcting it thanks to deformable mirrors in real-time [2]. However, because the atmosphere changes milliseconds by millisecond, the AO system must operate at extreme speeds. This requires a closed loop running at kilohertz (kHz) rates to effectively “freeze” and correct the turbulence.

The performance of an adaptive optics system is strictly limited by the speed and sensitivity of its Wavefront Sensor (WFS) camera. In SSA applications, where targets are often fast-moving and faint (magnitude 10 or dimmer), the WFS camera must operate in a photon-starved regime without introducing latency or noise.

Leading research institutions, including the Australian National University (ANU) and the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI), have standardised on the Andor OCAM2K to solve this specific engineering challenge.

They leverage three specific OCAM2K capabilities to turn their telescopes into precision instruments:

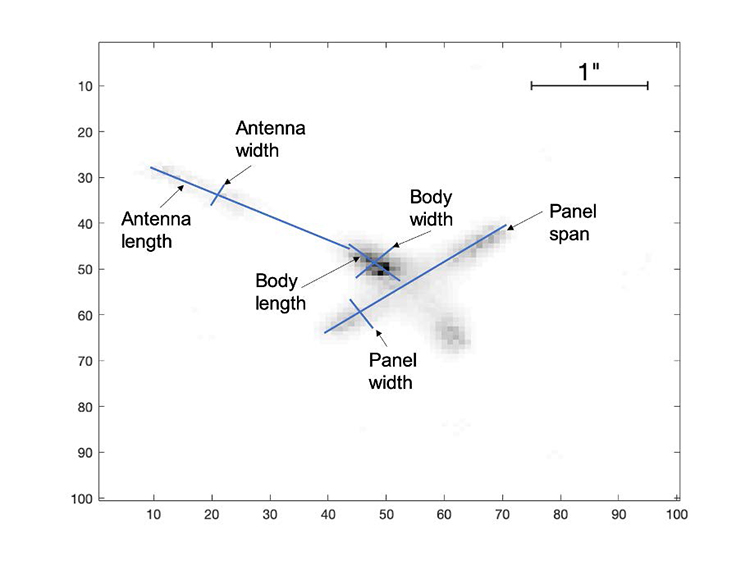

The Korea Astronomy and Space science Institute (KASI) developed an AO system for their 100cm telescope to image space objects at altitudes up to 1,000 km. Their primary goal was to determine the “size, shape, and orientation” of debris to improve ballistic coefficient estimation [2].

Using the OCAM2K to guide on the object itself (Natural Guide Star mode), KASI achieved measurable operational improvements.

Note on Natural Guide Star mode: Traditional AO often relies on a bright star nearby or a laser beacon to measure atmospheric distortion. However, in “Natural Guide Star” mode, the system uses the sunlight reflecting off the target satellite itself as the reference point. This allows the system to track objects even where no suitable background stars exist.

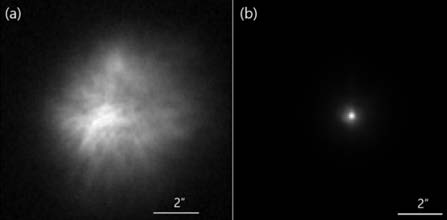

Figure 1: Comparison of stellar object imaging [2]. (a) Without AO correction. (b) With AO correction enabled. The stellar object appears to be better resolved on the image thanks to the AO system.

The Australian National University (ANU) deployed their “Adaptive Optics Imaging” (AOI) system on a 1.8m telescope to characterise LEO and GEO satellites. The ANU research team identified the OCAM2K as the “ideal choice” for the WFS, noting that “no other camera is capable of the same performance” [1].

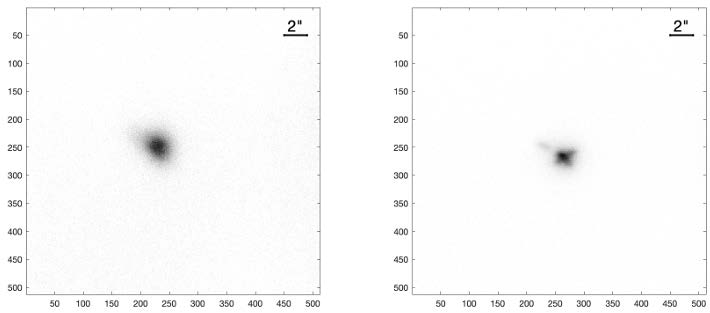

The system proved its value by imaging the Cosmos 1656, a defunct Tselina-2 satellite:

Figure 2: Adaptive Optics Correction of the Cosmos 1656 satellite [1]. Left: Uncorrected open-loop image. Right: Closed-loop image using the OCAM2K-driven WFS, resolving the solar panel array and body structure.

Figure 3: Cosmos 1656 image: shape and angular/physical size analysis.

For Space Situational Awareness, the ability to resolve a satellite’s geometry is the difference between a generic alert and a precise collision avoidance manoeuvre. As demonstrated by the KASI and ANU deployments, the Andor OCAM2K is the enabling technology for high-bandwidth Adaptive Optics. Its unique combination of 2 kHz speed, negligible latency, and sub-electron noise allows SSA systems to beat the atmosphere, protecting critical space assets.

Date: December 2025

Category: Application Note