Resources

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Expand

Collapse

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Part of the Oxford Instruments Group

Global bandwidth demand is outstripping Radio Frequency (RF) spectrum capacity. Facing this “spectrum crunch”, operators are pivoting toward Free-Space Optical (FSO) communications. By utilising optical carrier waves, FSO offers terabit-class bandwidth, unlicensed spectrum usage, and enhanced security for ground-to-space links [1].

However, shifting from RF to Optical introduces a physical challenge: atmospheric turbulence. Optical beams are highly susceptible to refractive index fluctuations caused by thermal gradients. This distorts the wavefront, preventing receivers from effectively coupling laser light into the Single-Mode Fibres (SMF) required for modern telecom infrastructure [1].

Research by Sorbonne Université and the University of Padova has validated a compact solution to this “coupling deficit”. Moving away from bulky reflective optics, the team demonstrated a transmissive Adaptive Optics (AO) system. Enabled by the high-speed C-RED 3 SWIR camera, this system “froze” and corrected severe turbulence in real-time. The system quadrupled fibre coupling efficiency and drastically reduced signal fading, even under extreme conditions simulating the vertical air currents of a ground-to-space link [1].

To achieve data rates exceeding 100 Gbps, FSO terminals must utilise standard telecom components like Erbium-Doped Fibre Amplifiers (EDFAs). These components require light to be contained within a Single-Mode Fibre (SMF).

This presents a geometry problem. The core of a standard SMF is microscopic, typically 10.4 µm in diameter [1]. Injecting light into this core requires focusing the incoming laser beam down to a diffraction-limited spot. In a vacuum, this is trivial; in the atmosphere, it is extremely difficult.

As the laser propagates, it encounters air pockets of varying densities. There refractive index inhomogeneities create scintillation, distorting the planar wavefront into a chaotic “speckle pattern” [3].

This results in two failure modes:

Figure 1: The FSO challenge. Atmospheric turbulence distorts the planar wavefront, preventing the receiver from focusing the energy into the fibre core.

To mitigate these effects, the industry has converged on the Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) band, specifically 1550 nm. This choice is driven by three physical advantages:

1. Atmospheric transmission: SWIR wavelengths suffer less scattering than visible light, penetrating obscurants like haze and fog effectively to ensure higher link availability [2].

2. Eye safety: Corneal absorption of 1550 nm light allows operators to use lasers with significantly higher power densities than visible wavelengths, increasing the link budget [2].

3. Component maturity: Since 1550 nm is the standard for terrestrial fibre networks, FSO engineers can leverage a mature supply chain of off-the-shelf telecom components [2].

However, standard silicon sensors are blind to this wavelength. To detect and correct wavefront errors, the system requires high-performance InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) sensors [2].

Most Adaptive Optics (AO) systems rely on Deformable Mirrors (DMs). While precise, DMs reflect light, necessitating complex, folded optical paths. This adds bulk and alignment complexity, a major penalty for portable terminals or satellite payloads where SWaP (Size, Weight, and Power) is constrained [1].

The research team validated a different approach: Transmissive AO. By using active elements the light passes through, the optical train remains linear and compact.

The system utilises two key technologies:

1. Fast-Steering Prism (FSP): A fluid-filled prism that tilts to counteract gross beam wander (tip-tilt). It consists of two glass windows separated by a transparent gel, actuated by piezo elements [1].

2. Multi-Actuator Lens (MAL): A liquid-filled lens serving as the primary correction element. Driven by 18 piezoelectric actuators, the MAL physically deforms to counteract higher-order aberrations like astigmatism and coma [1].

To maintain a stable link, the control loop must measure the distorted wavefront and shape the MAL before the atmosphere shifts again. This requires a sensor combining high SWIR sensitivity with extreme speed [3].

The C-RED 3 (First Light Imaging / Oxford Instruments) was selected as the Wavefront Sensor (WFS) engine to address three bottlenecks:

The C-RED 3 features a VGA (640 x 512) InGaAs sensor with high Quantum Efficiency (>70%) across the 900-1700 nm band [2]. This allows direct imaging of the 1550 nm signal without frequency conversion.

Speed is critical for “freezing” turbulence. The C-RED 3 operates at 600 Frames Per Second (FPS) in full resolution. For demanding scenarios like tracking Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites, the camera supports cropping. By reducing resolution to a 32 x 4 pixel Region of Interest (ROI), the camera achieves frame rates up to 32 kHz, ensuring loop bandwidth exceeds atmospheric coherence time [2].

Unlike bulky, cooled scientific systems requiring mechanical shutters, the C-RED 3 is uncooled and filter-free [2]. Crucially, it features on-the-fly adaptive bias correction. This algorithm compensates for temperature variations in real-time, removing the need for manual calibration, vital for remote outdoor terminals [2].

Figure 2: The C-RED 3 SWIR camera. Uncooled and filter-free, it provides the low-latency imaging required to drive real-time adaptive optics loops.

To evaluate the architecture, the researchers deployed a 100-metre free-space link and tested the system in two distinct scenarios: a baseline daytime test and a severe “Fire” test.

In standard daytime conditions, thermal convection creates moderate turbulence.

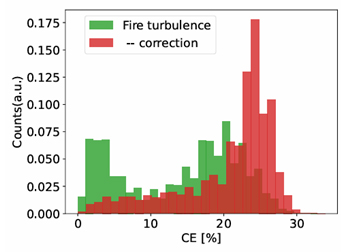

To simulate the harsh, anisotropic turbulence of vertical ground-to-space links, the team introduced a strong refractive gradient by lighting a fire directly under the optical path [1]. Rising heat and smoke created strong vertical air currents, representing a worst-case scenario.

Despite chaotic conditions, the C-RED 3 successfully tracked wavefront errors.

Figure 3: Power distribution histograms from the 'Fire' test [1]. The Green distribution (uncorrected) shows a spread-out signal with frequent dropouts. The Red distribution (corrected) shows a stable, Gaussian profile with significantly improved coupling efficiency.

The future of high-speed global connectivity depends on FSO reliability. This research demonstrates that massive, mirror-based observatories are not required to achieve that reliability.

By combining the linear compactness of transmissive optics with the speed and SWIR sensitivity of the C-RED 3, engineers can build portable, embedded optical terminals. These systems can deliver terabit-class connectivity, threading the needle into a single-mode fibre even when the atmosphere attempts to break the link.

[1] M. Schiavon et al., “Multi-Actuator Lens Systems for Turbulence Correction in Free-Space Optical Communications”, Photonics, vol. 12, p. 870, 2025.

[2] First Light Imaging, “Free Space Optical Communications and Adaptive Optics with C-RED 3”, Oxford Instruments Learning Centre, 2020.

[3] First Light Imaging, “Wavefront Sensing and Adaptive Optics with First Light Imaging Cameras”, Oxford Instruments Learning Centre, 2023.

Date: January 2026

Category: Application Note